Potassium diformate — animal antibiotic replacement for growth promotion

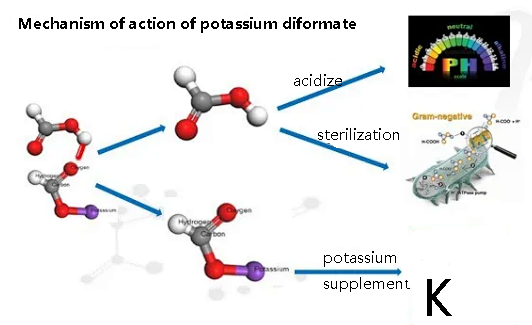

Potassium diformate, as the first alternative growth promoting agent launched by the European Union, has unique advantages in bacteriostasis and growth promotion. So, how does potassium dicarboxylate play its bactericidal role in the digestive tract of animals?

Due to its molecular particularity, potassium dicarboxylate does not dissociate in an acidic state, but only in a neutral or alkaline environment, releasing formic acid.

As we all know, the pH in the stomach is a relatively low acidic environment, so potassium dicarboxylate can enter the intestine through the stomach by 85%. Of course, if the buffer capacity of the feed is strong, that is to say, the acid strength is high, part of the potassium dicarboxylate will be dissociated to release formic acid and give play to the effect of Acidifier, so the proportion of reaching the intestines through the stomach will be reduced. In this case, potassium dicarboxylate is an acidifier!

All acidic chyme entering the duodenum through the stomach must be buffered by bile and pancreatic juice before entering the jejunum, so as not to cause great fluctuations in jejunal pH. At this stage, some potassium diformate is used as acidifier to release hydrogen ions.

Potassium diformate entering the jejunum and ileum gradually releases formic acid, some formic acid still releases hydrogen ions to slightly reduce the intestinal pH value, and some complete molecular formic acid can enter the bacteria to play an antibacterial role. When reaching the colon through the ileum, the proportion of the remaining potassium dicarboxylate is about 14%. Of course, this proportion is also related to the structure of the feed.

After reaching the large intestine, potassium diformate can exert more antibacterial effect. Why?

Because under normal circumstances, the pH in the large intestine is relatively acidic. Under normal circumstances, after the feed is fully digested and absorbed in the small intestine, almost all the digestible carbohydrates and proteins are absorbed, and the rest is some fiber components that cannot be digested into the large intestine. The number and variety of microorganisms in the large intestine are very rich. Their role is to ferment the remaining fiber, and then produce short chain volatile fatty acids, such as acetic acid, propionic acid and butyric acid. Therefore, formic acid released by potassium diformate in acidic environment is not easy to release hydrogen ions, so more formic acid molecules play an antibacterial effect.

Finally, with the consumption of potassium diformate in the large intestine, the whole mission of intestinal sterilization was finally completed.